TL;DR:

- No datatype will ever be able to represent all numeric values perfectly

- Rounding errors will always exist

- JavaScript uses floating-point numbers which are sufficient for many use cases

- If this is not sufficient for your use case... JavaScript might be the wrong choice!

Demonstration of the Problem

What do you get if you multiply 0.1 by 0.2? If you got 0.02, you are correct! Here is a gold star ⭐️ If you didn't... see me after class.

But what about in JavaScript?

0.1 * 0.2 = 0.020000000000000004

Go ahead and try this in your browser console if you don't believe me.

So clearly something fishy is going on 🤨

What is a number?

To fully understand this problem, we are going to begin by defining what we mean by "a number", and later we'll demonstrate how this is fundamentally incompatible with computation.

The Naturals

Let's start with the easiest type of numbers: The Naturals. These are more plainly understood as "the counting numbers". When we count "1, 2, 3, 4..." we are counting Naturals.

Near the end of the 19th century Giuseppe Peano provided a formal definition of the Naturals using 9 axioms. I won't bore you with all of them now, instead, I'll give you the severely abbreviated version. There are two claims:

- Zero is a natural number

- ... and then there are the others

No really, that's pretty much it. Most of Peano's axioms deal with narrowing in very precisely on what we mean by the others. But if you have learned to count, then you have learned The Naturals.

The Integers

God invented the integers, the rest is the work of man

— Leopold Kronecker

So far we only have positive numbers. If we want to include negative numbers (we do) then we need to define The Integers. We can summarize their definition as:

- Zero is an integer

- Positive naturals (defined above) are integers

- For every positive natural

n, there exists-n

Simple! Note that every Natural is also an Integer, but the reverse is not true.

The Rationals

If all we ever wanted to do was addition, subtraction, and multiplication, the above would be sufficient. However, as soon as we include division, we will need fractions. Consider for example what is the result of 3 divided by 2? Can you express that result in terms of a Natural or an Integer? Nope! So we devise a larger set of numbers like so:

For every integer a and every non-zero integer b then a / b is a Rational.

Note the specific callout to prohibit division by zero.

We can now happily work with addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division (except division by zero) ... and nothing will ever go wrong I'm sure... certainly the Ancient Greeks believed this, and based all of their mathematics on rational numbers. But they encountered a problem, which cannot be solved with rational numbers. Namely "What is the square root of 2?" Equivalently: What number, which when multiplied by itself equals 2? Although such a number exists, it cannot be represented as a Natural, or Integer or even Rational. It is something entirely different.

There's a probably apocryphal story that when Hippasus first proved that root 2 cannot be represented as a fraction, he was on a boat at the time, and his fellow mathematicians were so offended by this proof that they threw him overboard.

The Irrationals

The square root of 2 is Irrational but it's not the only Irrational, here are some other examples that come up pretty often in mathematics:

- The square root of any

Integerthat is not a perfect square - π (The ratio of a circle's circumference to its radius)

- ϕ (The Golden Ratio)

- e (The base of the natural logarithm)

You can think of Irrationals as anything that is, not a rational number i.e. anything that can't be represented as a fraction.

Countability

Before we consider how to represent numbers on computers, we first need to consider one very important property of sets: Countability. A set is Countable if and only if there exists some way to enumerate the whole set. Intuitively most sets are countable exactly because we can count them (hence the name). But not every set is countable. The set of all colors for example is not countable. There is no way for me to count the set of all colors unless I narrow it to some finite collection.

Consider the sets of numbers we have seen so far:

The Naturals are countable, as demonstrated by how we literally learn to count them.

The Integers are countable, but it takes a little trick. If we only count upwards from zero (or one) we will never count the negatives, but if instead, we count by alternating between positive and negative:

0, 1, -1, 2, -2, 3, -3,...

Then we will count every Integer. Note how the order of countability is not important, only that some sequence can be defined that visits every member of the set.

The Rationals are countable, but it takes an especially smart trick. Every Rational is equivalent to some pair of Integers: a / b. We could construct a 2D grid therefore of every Integer a on the x-axis and every Integer b on the y-axis. Then the set of Rationals is equivalent to the set of all grid points in this 2D plane. We can count all the points on the plane by spiraling outwards from the center along diagonal lines. In this way, we demonstrate that the Rationals are countable.

Unfortunately, the Irrationals are not countable. It is not that we haven't yet found a way to count them... but rather it has been proven that no method of counting Irrationals can ever exist. The proof is particularly tricky, but was proved in at least two different ways by Georg Cantor in the 19th century.

We now know everything we will need to know about numbers before talking about computation.

How do we represent numbers?

How do we represent anything?

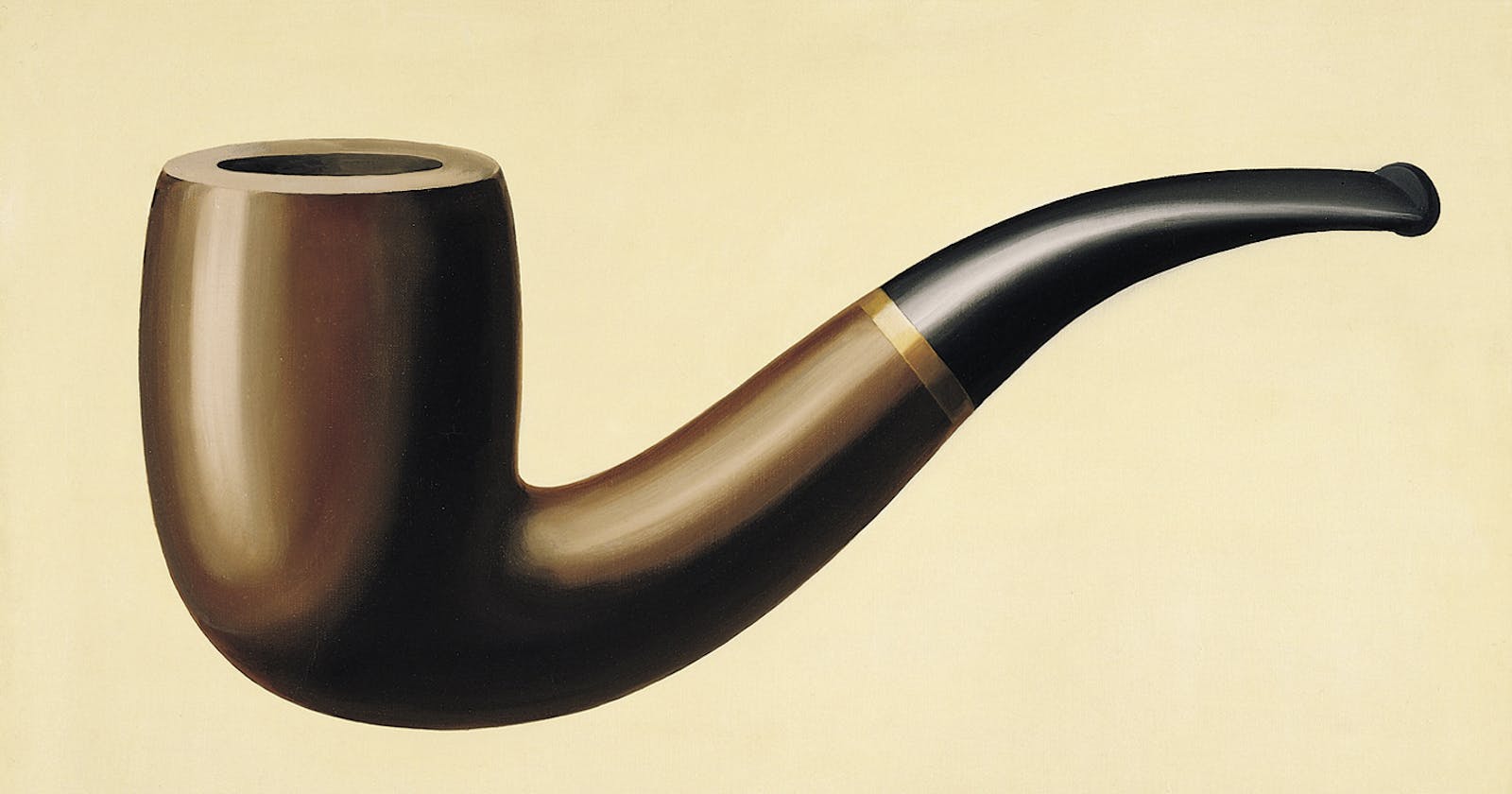

Ceci n'est pas une pipe

— "The Treachery of Images" by Magritte

Defining a number is not the same as representing a number. "0" is not zero. It is a symbol. As programmers, we are concerned with the representation of numbers on computers. When we perform computation on numbers we take as input some symbols e.g. 1 + 2, manipulate those symbols, and then return or display some symbols corresponding to the result of our computation e.g. 3. But ultimately it's symbols all the way down. This distinction between symbol and mathematical number is not usually important and we can put it out of our mind, but today we'll be digging into that distinction to reveal a fundamental limitation of computation.

How do we represent data on a Turing machine?

Why should we care about Turing machines? I could hypothetically explain everything about how numbers are represented on my exact computer's hardware and in turn how exactly this is handled by my operating system and any other software. But this might not say anything meaningful about the representation of numbers on your hardware and software. This is why Turing Machines are a useful device for reasoning about the principles of computation. Turing Machines are an abstraction for reasoning about computation in general without reference to any specific hardware or software in particular. Additionally, any claim or proof we can make in terms of a Turing machine will never age or become outdated.

So let's remind ourselves of the basics of a Turing Machine. Turing Machines have an alphabet (a finite set of symbols), which can be read from and written to an infinite tape of memory. Whatever data I choose to store on that tape must therefore be represented in terms of combinations of symbols from our chosen alphabet. I could for example represent Naturals as combinations of the following symbols:

"9", "8", "7", "6", "5", "4", "3", "2", "1", "0".

And indeed this is exactly what we do when we do "computation" by hand with pencil and paper. If we include the symbol "-" then we can also represent Integers. But regardless of our specific choice of scheme for representing numbers, we want our representations of numbers to be expressed in terms of finitely long combinations of symbols from a finite set of different symbols. Every finite set is countable and every finite combination of members from a finite set is also countable, i.e. the set of all things we can ever represent on a Turing Machine is countable.

You will recall from earlier that although the Naturals, Integers and Rationals are countable, the Irrationals are not countable. It follows therefore that the set of all Irrationals can never be represented with absolute precision on a Turing Machine no matter what symbolic scheme we use. Any attempt to represent the Irrationals on a Turing Machine requires some approximation, effectively reducing the size of the set of Irrationals to something countable but in a way that neglects some values, and yields rounding errors.

Floating Point

JavaScript uses a double-precision (64-bit) binary floating-point format for its default number type. It is known as a "double" for historic reasons since early implementations of floating-point numbers in other programming languages used just 32-bits, but the essence of the format remains the same. There are two key insights to understanding the floating-point representation of a number.

- Everything is represented in binary, i.e. we use only the symbols

0and1 - Every value can be represented as some leading digits multiplied by a power of 2

We call the leading bits the "Mantissa" and the power of 2 the "Exponent".

To demonstrate this, consider the following numbers:

5 in binary is 101:

- Mantissa: 1.01

- Exponent: 10

Note that the exponent is also in binary so "10" here is not "ten" but rather "two".

9 in binary is 1001:

- Mantissa: 1.001

- Exponent: 11

7/32 in binary is 0.00111:

- Mantissa: 1.11

- Exponent: -11

This format has the advantage of being very flexible in accomodating both very large and very small numbers. It is called Floating Point because the point in the number can float up or down to wherever the first leading bit will be, e.g. in the last example we float the point down by three places by using a -3 exponent. Now let's consider what happens when we try to evaluate the expression:

0.1 * 0.2

First, we convert the numbers to their floating-point representations:

0.1 in binary is 0.00011001100...:

- Mantissa: 1.1001100...

- Exponent: -100

0.2 in binary is 0.0011001100...:

- Mantissa: 1.1001100...

- Exponent: -11

You might already see a problem, that our numeric representations have become an infinite sequence of symbols. In general for any base number system, a Rational will expand to an infinite sequence if the denominator is not a divisor of any power of that base. In this case, 0.1 "one-tenth" is not a divisor of any power of 2, so in binary it expands to an infinite sequence. If you are interested in this little bit of number theory, you'll notice bases with more factors require infinite expansions less often. Six is especially good.

Then to complete our computation, we multiply the mantissas together and combine the exponents, which leaves us with:

0.0000010100011110101...

- Mantissa: 1.0100011110101...

- Exponent: -110

Unfortunately, we had to truncate our infinite expansions before performing the multiplication, and then also the result must be truncated. This is how rounding errors sneak into our computation.

Critiques of JavaScript

There are valid critiques to make of JavaScript... but rounding errors isn't one of them. The rounding errors follow inevitably from a fundamental limitation of computation.

On the other hand, JavaScript could have included alternative numeric data types. Many other programming languages offer a variety of numeric types, to better support different use cases. I would especially like a Rational number type which perfectly represents all Rationals as tuples of integers with perfect accuracy and no rounding errors. I could of course implement this for myself (and have done in the past!) but this loses out on a lot of speed optimizations for existing primitive number types; there's a reason computer speed is often measured in floating-point operations per second, the industry is in love with floating-point numbers and optimizing for them, despite their glaring weaknesses.

JavaScript did add the BigInt a couple of years ago, but it is primarily intended for supporting especially big integers (unsurprisingly). This does not save us from our multiplication rounding problem.

So long as we must work with floating-point numbers, we will suffer from rounding errors. I'm a firm believer that we shouldn't forget JavaScript was only ever intended to be a simple browser scripting language, and we shouldn't treat it as the solution to every problem. If your project needs more precision than you can get from a float, consider doing your primary computation in a different language (perhaps on a server) and treating JavaScript only as a means to retrieve and display human-readable values in a frontend.

Choose the right tool for the job.

Take care,

Rupert